A Grand Canal Palazzo Returns to the Market After Restoration

Set directly on the Grand Canal in Dorsoduro, Ca' Dario is one of Venice’s most recognizable private palazzi—and one whose return to the market with Engel & Völkers Private Office merits attention.

Ca’ Dario on the Grand Canal, positioned between the Accademia and the Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute in Dorsoduro.

The palace was commissioned in 1489 by Giovanni Dario, secretary to the Venetian Senate and a senior envoy to the Ottoman court under Mehmed II, following his successful negotiation of peace and trade agreements between Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Those agreements brought Dario both political standing and the means to build on the Grand Canal. The architecture reflects that background, moving away from Venetian Gothic convention toward a more measured Renaissance language shaped by Dario’s international diplomatic life.

The influence here isn’t Ottoman ornament or exotic motifs. It’s confidence and early adoption. At a time when much of Venice was still building in a late Gothic idiom, Ca’ Dario’s Grand Canal façade instead favors symmetry, proportion, and balance over vertical emphasis. Attributed to Pietro Lombardo, the façade’s polychrome marble inlays, circular stone motifs, and crisp surface articulation align it with the humanist architecture circulating through Italy and the eastern Mediterranean. This approach was not yet standard in Venice and points to an owner looking beyond local convention, using architecture to project authority rather than decoration.

That contrast continues at the rear. Facing Campiello Barbaro, the palazzo retains its Gothic arches, chimneys, and loggia—an intentional split between public and private faces. Toward the Grand Canal, the building presents a formal, outward-looking identity; behind, it remains grounded in Venetian tradition. The result is a palazzo that reflects both the city’s global reach and Dario’s position within it.

In the late 19th century, Ca’ Dario entered a new phase of stewardship under Countess Isabelle Gontran de la Baume-Pluvinel, who restored the interiors with a clear Renaissance sensibility while preserving the palazzo’s original scale and proportions. This period ensured the building’s continuity as a private residence rather than a subdivided artifact.

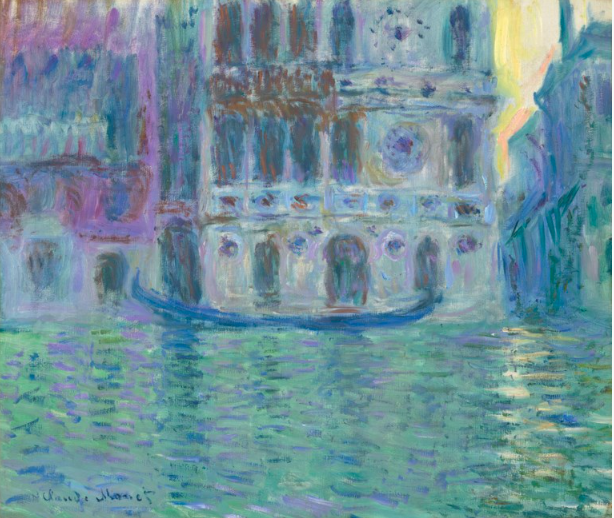

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Le Palais Dar

The palazzo’s presence on the Grand Canal also drew artists: in 1908, Claude Monet painted a series of studies of the façade, drawn to its color, rhythm, and relationship to the water. Within Dorsoduro, the setting remains notably residential, close to major cultural institutions yet removed from Venice’s most congested routes.

Ca’ Dario has long been associated with a popular narrative describing it as a “cursed” palazzo—a reputation built from a series of loosely connected anecdotes involving former owners and occupants. Historians note that many of the events most often cited occurred elsewhere, years after any association with the building, or involved individuals who were never full-time residents. In Venice, where centuries of aristocratic life were shaped by political instability, financial reversals, and short life spans, similar stories can be attached to many historic palazzi. What distinguishes Ca’ Dario is not an unusual concentration of documented events, but the way unrelated episodes were later grouped together and repeated—particularly during extended periods when the building stood vacant and without a clear future. Today, that mythology sits at odds with the palazzo’s documented history and present condition. With its structure consolidated and its next use clearly defined, Ca’ Dario is best understood not as folklore, but as a significant private residence that has endured—and adapted—across five centuries of Venetian history.

The palazzo now returns to the market following major structural restoration works, including comprehensive interventions to the roof, façade, foundations, and primary structural elements. In Venice, where engineering complexity and regulatory oversight make such projects rare, this phase represents the most technically demanding and capital-intensive part of any restoration. The building stands structurally secured for long-term use. Portions of the interiors retain historic detailing and finished rooms, while other areas are intentionally left open—allowing a future owner to complete the interior fit-out according to their own requirements without compromising the building’s integrity.

Arranged across four levels and spanning approximately 1,055 m² (11,356 sq ft), the palazzo includes two noble floors with grand reception rooms overlooking the canal, formal spaces such as the Sala Maometto, a library and service areas, and nine bedrooms with eight bathrooms. Contemporary amenities—including a private cinema, wine cellar, and elevator—are integrated discreetly within the historic envelope. A private walled garden, panoramic terrace, and direct access to the Grand Canal via a private dock further distinguish the residence.

Across Europe, ultra-luxury hospitality groups are once again underwriting historic properties once considered too complex to modernize. From Venice to Paris, palazzi and hôtels particuliers are being structurally restored at scale—quietly validating these assets for contemporary use and, by extension, for the private market. Globally, high-net-worth buyers are showing growing interest in properties that combine the scale and privacy of private homes with hospitality-level service. Whether through branded residences affiliated with luxury hotel groups or fully serviced villas offering concierge, chef, and housekeeping support, this shift reflects a preference for discretion and bespoke experience alongside traditional high-end hospitality.

Recent and forthcoming projects by Aman Venice, Rosewood Hotel Bauer, and Nolinski Venezia reflect a broader recalibration of Venice’s luxury landscape—one that favors permanence and stewardship over short-term conversion. Within Italy’s prime property market, this has reinforced the value of historically significant buildings that have already absorbed the most complex phase of restoration.

In that context, Ca’ Dario stands out not as a finished product, but as a structurally prepared Grand Canal palazzo—rarely available, increasingly difficult to replicate, and aligned with how Venice’s most important historic properties are being re-used today.

All photos belong to the listing agency.